A Brief History of DCM

Years ending in five have special significance to Donaldson Capital Management. In 1975, I (Greg) left Indiana Bell and joined a small Indianapolis-based bond firm, Traub and Company. In 1985, I entered the money management business for the first time, when I helped start Raffensperger, Hughes Investment Advisors (RHIA). A decade later in 1995, I formed Donaldson Capital Management. If you have done your math, that means I am celebrating three anniversaries this year: thirty years in the investment business, twenty years in the investment management business, and ten years in the firm bearing my name. A handful of you reading this letter have celebrated all of these anniversaries with me, others have been aboard for a shorter time, and many of you are new arrivals whom I have yet to meet. To all of you, and those who have gone before us, I want to say thank you. You have been a blessing to my family and me. You have taught me the wonder of how trust is formed in a world too full of doubt and betrayal. I thank God everyday for the privilege of serving you.

At the occasion of these multiple anniversaries, I wanted to share some of the milestones along the way that have marked and shaped the firm we are today. Although the early part of this story is mostly about my experiences in the investment business, the DCM story has moved far beyond me. Indeed, President, Mike Hull, and Vice-President of Operations, Laura Roop, run the day-to-day business. I serve as the Director of Portfolio Strategy and one of the portfolio managers.

1975 – Thirty Years Ago

When I joined Traub and Company in 1975, OPEC had just dramatically raised oil prices, stocks were in a steep decline, and inflation was exploding. To top it off, Traub and Company dealt mainly in bonds, which were about to start their worst bear market in history. None of these impediments slowed the firm a bit. Traub was full of young people in their 30s and 40s, who were incredibly focused, hard working, and collectively knew bonds better than any group of people I have ever known. We were all TnT people. We each covered a territory; we left every Tuesday morning to visit clients and returned Thursday afternoon. We called on banks, insurance companies, municipalities, and wealthy individuals – what we called professional buyers. They joked about my territory. It extended from Louisville to St. Louis and south all the way to the Gulf of Mexico. My road warrior life improved dramatically when I opened an office in Evansville, which was three hours closer to my territory than was Indianapolis.

Traub believed that to know bonds, cold, you had to know the economy, cold or hot, and they did. There are still dozens of former Traub employees inhabiting the major bond houses throughout the Midwest and South. I have maintained relationships with many of these people, and today Donaldson Capital Management buys many of its bonds from these old fashioned bond guys.

Traub knew bonds, but they were the first to admit they were not experts in stocks. In the early 1980s, I became convinced that Fed Chairman Paul Volker would tame the runaway inflation, creating a good environment for stocks, which had languished for years. I tried to convince Mr. Traub that we should build some know-how in high quality stocks, not just local issues, as was the case then. He acknowledged that a better stock market was coming, but the firm’s expertise was in bonds, and the company was already growing as fast as he felt was safe. With this in mind, I started looking around for a firm that knew stocks but also possessed a solid bond department. As I searched, I kept hearing the name Gene Tanner. He was the president of Raffensperger, Hughes, which was just down the street from Traub. Tanner was reputed to be the biggest broker in Indianapolis, and he also ran a respected firm. At first, I shied away from talking with him because he had such a big reputation in the industry. However, after interviewing a half dozen firms, including two on Wall Street, it became clear to me that if I wanted to learn from the best and stay in the Midwest, Gene Tanner was the guy to talk to.

When I met with Mr. Tanner, I told him about my desire to learn more about stocks, and asked him if I joined his firm would he help me learn. He laughed and said he would do what he could, but lately he had been thinking he needed to find someone who could teach him. I remember thinking how odd that was coming from someone with his reputation. But if I thought that was odd, what he said next was almost shocking. As we were wrapping up our meeting, I asked him if he would mind sharing with me what he thought was responsible for the success of his firm. He sat back in his chair, folded his hands, looked out the window, and said, “Being a nice person goes a long way.” And then he added, “In the long run, this business rewards honesty and integrity.”

I joined Mr. Tanner in 1981, and in some ways, I still work for him to this day. His self-deprecating way and humility are genuine and have never changed. The best news, however, is that he is still teaching me about stocks and the ways of Wall Street. This year he celebrates his 47th year in the investment business, as Vice-Chairman of NatCity Investments.

1985 – 20 Years Ago

In 1985, I served as the Director of Sales and Marketing for Raffensperger, Hughes. During the year, I worked closely with Gene on a strategic plan. The stock market was strong and bond yields were falling. I argued that the time was right for Raffensperger to start a portfolio management division. There were only a handful of true money management firms in our area, and I believed that professional management of stocks would become increasingly desirable for wealthy individuals. I cited some statistics of the time showing that in the late 1960s individuals had over 40% of their assets in stocks or mutual funds. That figure had fallen to only about 20% in the mid-1980s. The extremely high interest rates of the 1970s and early 1980s had pulled huge dollars out of stocks into bonds. Now, however, with bond yields falling rapidly, people would be pushed back to stocks, especially since President Reagan had lowered capital gains taxes. My strongest argument was this: Managing a million dollar portfolio of stocks was not possible for most people. There were just too many variables in purchase and sell decisions, and the markets were too volatile. Individual investors might have a fighting chance to develop bond management skills, but to do so in stocks called for intense study and experience, something that could get very expensive for a novice to learn.

After only a few meetings, he blessed my idea of starting a money management division, and late in 1985 Raffensperger Hughes Investment Advisors (RHIA) was born. I was the first senior officer, and by early 1986, I had assembled a small team to market our services and manage portfolios. By the middle of 1987, RHIA’s assets had grown to $30 million. Our growth had been greatly helped by stocks being up nearly 45% in the first six months of the year. That was about to change in a way no one could have imagined. At that time RHIA used what we called a B-I-G investment strategy. We invested in Big companies that were Industries leaders and whose earnings were Growing. Our buy and sell disciplines were momentum driven: ride your winners, cut your losers.

October 19, 1987, Black Monday, was surreal, agonizing, devastating, and yet, in some ways the best thing that ever happened to me. On that one day, the Dow Jones fell 23.7%, which would be equivalent to about 2500 points today. For the month of October 1987, the Dow fell nearly 30%. I wrote in my journal that I felt like the school bus driver who lost control of his bus and drove it over the cliff, losing all the children in the neighborhood.

In the days immediately following the crash, I talked with every client we had many times, trying to reassure them, but by the end of the week, I was listening to what I was saying to see if I could reassure myself. Since I had no internal compass to tell me what a stock was really worth, did I have the right to encourage people to stay in the market? Weren’t stock prices efficient, in the sense that there were millions of buyers and sellers making educated guesses about the prospects for the company? Didn’t today’s price reflect the net best guess of what the company was worth? As I said earlier, in those days, I was a momentum stock investor, and now the momentum was straight down. Yet, something inside me said the right thing to do was to buy.

The main reason for this feeling was prompted by a telephone call with a bond salesman. He explained that he needed a bid on some Indiana University bonds for a customer who insisted on selling. He said the bond market had frozen up about like the stock market. My recollection is that he had about $200,000 of the bonds and needed to sell them by the end of the day. I had a general idea of what the bonds were worth, and I had no fears of Indiana University defaulting. They were safe. Interest rates had been going through the roof in recent weeks, but the stock market crash had produced a flight to safety, causing bond prices to begin to rally. The toughest part of the IU bond was that it matured in 30 years. After thinking about it, I realized come heck or high water, if I could buy the bonds to yield 10%, I had a real bargain.

I called the guy, gave him my price, and he took it.

That night as I lay in bed, I was both enlightened and indicted. I knew how to value a bond, and even in this difficult time, I knew a good value when I saw one, and I could step up to the plate and buy it. But when it came to stocks, I had no similar way to compute intrinsic value, and not having this, I was forced to wait for the dust to clear before I got back in the market. The best I could do was to identify those companies whose financial strength and brands would likely carry them through these uncertain times.

I vowed that I would find a way to determine intrinsic value, and the next time the market was throwing away good companies at bad prices, I would be a buyer instead of a watcher. What I found in my long search for a method to determine the intrinsic value of a company has changed my whole attitude about stocks. Today, I believe the market regularly overreacts both up and down, and patiently “waiting for your price” is rewarded.

RHIA survived the crash of 1987; indeed, we seemed to have benefited from it. In the wake of the crash, almost all the brokers and clients at Raffensperger, Hughes were totally confused. Since we were the firm’s money managers, it seemed only right that we would be called on to make sense of what was going on. We spoke on daily conference calls, calls with important clients, and fielded hundreds of questions from our money management clients. We told everyone who would listen the truth as we believed it to be: stocks were probably overpriced heading into the crash, but Black Monday was a financial accident caused by computerized trading at big Wall Street firms. We explained that the economy appeared to be relatively unaffected, so earnings should hold together. But, we concluded that the stock market was unlikely to quickly regain the losses it had sustained until investors were confident that such an accident would not happen again. As it turned out, most of our assessment of what had caused Black Monday was on target, but the market turned around much faster than we had guessed. In 1988, the S&P 500 grew by almost 17%. Our forecast was for less than half that figure. Why did the market turn so quickly? The main reason was that the biggest, most knowledgeable investors already understood that stocks had intrinsic value and how to compute it. Thus, they knew America was on sale at bargain prices and they bought.

From 1988 through 1993 RHIA’s clients and assets grew rapidly. We returned to our B-I-G investment strategy and our performance exceeded the benchmarks for the period. We did start a “value style” of investment management that used dividend-paying stocks, but it had few assets and no real emphasis. The rapid growth, in retrospect, was not a blessing. We found that we did not have the people or the systems to accommodate the growth, which caused our level of customer service to fall dramatically. I personally had more complaints of poor service during that time than at any time in my career. The complaints caught me by surprise, because our investment performance had been good, and I had always thought that was priority #1. I was about to learn the rest of the story, good client service might be hard for people to describe, but they know it when they are not getting it.

But the news would get worse. Our rapid growth had caught the eye of The Associated Group, a large affiliate of Blue Cross-Blue Shield, who owned Raffensperger, Hughes. The Associated Group spun RHIA out of Raffensperger, Hughes, merged it with their investment department, and renamed the entity Anthem Capital Management. RHIA had about $160 million of assets under management and eight employees before the merger. The new entity had over $2 billion under management and over 80 employees. Anthem started a trust company and a family of mutual funds, including a rising dividend fund that I managed. I had long believed that trusts, mutual funds, and investment management were natural partners. With these three service offerings, a large firm like Anthem could provide investment management to almost anyone. We were one of the first non-bank companies in the nation to put these three investment products under one roof. I have always said that Anthem got the “head” part of the business right, but they forgot the “heart.”

That deficiency in matters of the heart became increasingly apparent, and in short order, I knew that Anthem was not for me. One of the first indications was a change in our motto. RHIA’s motto of Discipline, Patience, and Humility was discarded as too corny. The beginning of our mission statement, which hung on the wall in our entry way, was changed from, “. . .[O]ur ultimate business is trust” to “[We] will earn a return on equity consistent with the leading firms. . .” The next clue came when a brochure appeared on my desk with a long quote attributed to me. The quote was not mine, and it was not something I would ever say. The final straw occurred in October of 1994 at our weekly investment strategy meeting. My title was Director of Economic Strategy. My primary responsibility was to develop an investment strategy for managing our bonds and other interest-sensitive securities. At the weekly investment strategy meeting I provided an overview of the economy and Federal Reserve policy and set guidelines for the quality and length of maturity of the bonds that we were buying.

1994 had been a tough year for bonds. Inflation had ticked up and the Fed was aggressively pushing interest rates higher. In December of 1993, long-term treasury bonds had yielded 5.75%, but here in October they yielded over 8%. I had been saying for several months that interest rates were much higher than they should be, based on historical relationships with inflation, and I expected them to fall. For this reason, I was advocating buying long-term bonds. Setting interest rate policy was my call. It was subject to debate, and everyone had an opportunity to offer their own views, but in the end, my job description said I set the policy. The debate at that October meeting was not pretty. I was reminded of having been wrong about the market for several months, believing too much in Alan Greenspan, and being bullheaded about it. Everyone is entitled to their opinions, but I knew few of the other five members of the investment policy committee had any idea where interest rates were going. They were mostly worried because bond prices had been falling for months, and indeed, they were starting to catch some worried questions from our clients. I had learned a lot about bonds and the economy from my days at Traub, but I had learned something even more valuable for negotiating tough times from Gene Tanner. He had always said, “Get the fundamentals right. In the short run, prices can go anywhere, and they will; but in the long run, they will follow the fundamentals. If you don’t have the fundamentals right, you’ll faint when you should be fighting.” There was no doubt in my mind that I had the fundamentals right, and therefore, I was not about to change my opinion to appease the other members of the committee, who I thought were in the process of fainting.

Because my view was seen to be in the minority, the chairman decided to take a vote. I do not know if he realized it, but in taking the vote on something that was clearly my decision, on a de facto basis, I was being relieved of my authority. Among the six votes, mine was the only one for my recommendation. As I looked around the room, I realized I had been outvoted by fear. Almost everyone had advanced degrees in business, one even had a national reputation, but I knew fear was whispering in their ears and not the principles of economics that they had learned.

1995 – 10 Years Ago

Donaldson Capital Management was conceived that same day on the long drive home to Evansville. It may seem as though I was responding like a sore loser, but there was something inside of me that was elevated more than my ire. It was as though I was lifted above the situation and saw it for what it was, and what I saw troubled me: I did not trust these people. They had put words in my mouth on the brochure and acted like it was nothing. They had rewritten the mission statement to put their own rate of return as their #1 priority, rather than their clients’ well being. But, most troubling to me was the realization that on this day they had bushwhacked one of their own.

At moments like these, it pays to have a friend and mentor like Gene Tanner. When Anthem Capital had been spun out of Raffensperger Hughes, he had remained as Raffensperger’s president. We had spent only a few minutes discussing the situation, when he said, “Come back here and start your own firm. You can do it, and I’ll help you. We’ve got extra space and technology. Just bring your own people and you’re in business.” Roughly 60 days later it was done . . . about the same time interest rates started a downtrend that would last almost 10 years. Within a year, almost all the people who had gone to Anthem from RHIA had left.

One of the first thoughts I had upon the forming of Donaldson Capital Management was how to get Mike Hull to leave Bristol Myers and join me. Mike was my best friend, and I had been recruiting him for a decade; but his ship just kept getting farther away from me, as he rose in the ranks of Bristol’s Mead Johnson Nutritionals division. After a two-year stint in China, he was now the Marketing Director for infant formula, a billion dollar plus product line. Mike and I had met on a three-day spiritual retreat in 1982, and even though we did not know each other, he and his family started attending our church shortly thereafter. Our kids became best friends first, and that led to our families beginning to spend time together at church and socially. I really got to know him over many years of walking the beach at Destin, Florida, where our families vacationed together each fall during the 1980s.

I had been recruiting Mike for such a long time because he had been in the investment management business earlier in his career, and before joining Bristol Myers, he had been the president of a small health-care products company. From all of those walks along the beach, I knew the job he had enjoyed the most was running the small firm. Our families had celebrated the year he was able to get his company’s eye-care solutions in Wal-Mart and Walgreen. I knew he had left the company to go to Bristol Myers mainly for the security a large firm offered his young family. But that security was coming at a stiff price. As he had moved higher in the organization, the choices were becoming less attractive: continue moving up and give the company more of his life or sit still and wait for Bristol to say they no longer needed him, like they were doing with so many others.

Most people knew Mike, at that time, as a bright and competitive executive, but I knew the brightest thing about him was his heart. I knew countless examples where Mike had gone out of his way to help someone in need, but there was one incident that I stumbled onto that left me speechless. I saw him in the cloak room of our church one Sunday after the service with two big bags of groceries. It was early summer and I knew of no food drives or church functions that would require him to bring groceries to church, so I asked him where the food was going. After some stalling, he finally admitted that he was taking the food to someone he had met in our Christmas food drive. He said, “You know, it occurred to me that that guy might get hungry at times other than Christmas.” Then he turned and left.

It was that heart that I wanted to work along side of and learn from. It was that heart, and the head that came with it, that I wanted to manage our little firm.

King Traub was the head of Traub and Company. He was a bigger-than-life type of character, and a genius at salesmanship. I can still hear him say, “No is not an answer that means no forever. It just means not now. Ask tomorrow and again next week, and keep asking until they tell you don’t ask again. Then ask them when you can ask again.”

I had followed King’s counsel to the letter in trying to hire Mike. He had told me no for a decade, but I knew his job with Bristol was wearing on him, so I decided to try him again. My sales pitch to Mike was simple: Come and join me. I will take care of the investments; you take care of running the firm. We will become as big as you decide. I can offer you about half of your present salary, but I can provide you with security that you will never have at Bristol Myers, because at Bristol, there will always come a day when they say goodbye, and that will never happen with me (I had borrowed this line of thinking from him). We need to add people. How many is up to you, and you have to figure out how to pay for them, but we need to grow. To my surprise he said yes. I remember saying something like, “Are you sure? You’d be giving up a lot of income.” (King would not have been proud of this approach.) He explained that he was sure, but he had some things that he needed to finish at Mead Johnson, and he could not join me for a year.

Mike joined our firm in February of 1997. He said he would like to study our business, the industry, and get to know our clients before he officially started to run the company. Near the end of 1997, he said he was ready to talk. The following is an excerpt of what he shared during the next few weeks:

There is a disconnect between what our industry thinks is most important to the clients and what the clients think. The Financial Services industry thinks that investment performance is the most important ingredient, but the clients think it is a trusting relationship and good service. Put another way, Wall Street thinks it’s all about how smart or savvy they are -- the head -- while what the clients want is someone who cares – the heart. To make matters worse, Wall Street keeps the investment selection process a closely guarded secret, shrouded in mystery and complexity, which has the effect of holding clients at arms length, when the client’s want to feel like they are a part of the process.

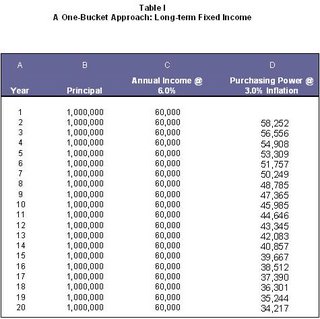

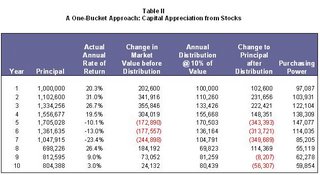

But the clients also are making a mistake. In their desire to find a trusting relationship, they often sacrifice a lot in investment performance. In essence, they pay too high a price for service and simplicity. The best examples of this are Certificates of Deposit and Fixed Annuities. These financial products are simple, usually sold by someone the clients knows, and do not fluctuate in price. What could be wrong with this? Nothing, if you are trying to share the wealth, but plenty if you are trying to live off of your assets for the rest of your life. Based on historical returns, at the rate of inflation, money will double in about 20 years, compared with almost an eight-fold increase in common stocks and almost a four-fold increase in corporate bonds.

Investors deserve a new model for financial services relationships. Let’s call it a heart and head strategy. The number one priority of our firm should be client satisfaction. To the clients that means a trusting relationship and good service. The way to accomplish this is to build a staff of people whose sole function is to respond to our clients’ questions, needs and concerns. These people should not be clerks. They should be smart, well-trained, friendly, and possess a servant’s heart. Our clients should be almost surprised by how well they are treated and how knowledgeable these client services people are. The goal should be to have our client services people on a first name basis with every client we have and be able to handle their needs on the first call. The heart of our business, unlike most investment firms, will be trust building through surprisingly good customer service.

Next, we must make the head part of our business, the investment process, more understandable and more transparent. We need to get our heads out of the investment clouds, look our clients in the eyes, and tell them what we are doing and why. We need to let them look over our shoulders and help them to see what we see. We need to show them that, even though what we do may not be simple, it is sensible, understandable, and has solid prospects for success. We should teach our clients the basics of how to value a company so that when increased volatility inevitably comes, they can see through it to the true value of a company, and not be drawn in or pushed out at precisely the wrong moment.

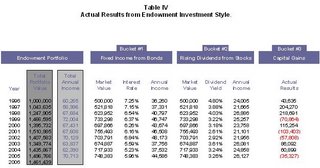

For these reasons, we should place more emphasis on the Dividend Strategy. There are very few people who have gone as far into dividends as you have, and I am convinced that the dividend strategy produces investment returns as good as or better than the market with far less volatility. But if we keep it to ourselves, we are doing the same thing that everybody else in the Financial Services industry is doing: mystifying the investment process and keeping our clients at arm’s length. If we are a heart-first company, we need to share what we have learned about dividends, especially as it relates to determining what a company is worth. For our clients’ wellbeing as well as our own, we need to teach them that the current selling price of a stock is almost never what it is really worth. We have simply got to get them out of the business of valuing their portfolios using their monthly statements or a website. There is very little correlation between what a company is selling for today and what it will be selling for next year or five years from now. On the contrary, we know in many cases, there is an 80%-90% correlation between dividend growth and price in a year or five years. In every way we can, we must get this information out to our clients and help them understand it.

Mike concluded with a far-reaching thought. “Over the next twenty years, more people than ever before will be retiring with a fixed sum of money that must last them the rest of their lives. Unless they become investors instead of speculators, and unless they learn how to invest for income as opposed to purely capital gains, retirement will be a nightmare for them. Our job is to reach them and share our story.

Over the past six years, we have been implementing Mike’s strategy for our firm. We promoted Laura Roop to Vice President of Operations and Client Services. Carol Stumpf is now the Director of Client Services. Laura and Carol, along with their fellow teammates, Tom Piper, Beth Dietsch, and Ciavon Fetcher, are the people Mike envisioned who would possess good heads and great hearts. All of these people have been with us for at least four years. Rick Roop, Laura’s husband, joined us as a third portfolio manager, and we are talking to yet another candidate. We have added a technology specialist to our staff, and we have added software that helps us measure the quantity and quality of our client interactions. We have simplified our investment management styles, and now everything we do in stocks is dividend oriented. We have written extensively about our ongoing dividend research and tried hard to make this understandable to our clients, new and old. Finally, we have added a process that assures each of our portfolios is as close to our “best idea” model portfolio as possible.

Today, Donaldson Capital Management serves nearly 300 families in 28 states and the District of Columbia with total assets approaching $300 million. Indiana continues to be the state where we have the most clients, but we have a growing presence in Michigan, Ohio, Kentucky, Tennessee, Georgia, Arkansas, Alabama, and Florida. We have relationships with over 40 brokers throughout these areas who refer business to us. Brokers in the South have been referring clients at such a pace that we plan on opening an office in either Nashville or Birmingham, during the next quarter.

That is the Donaldson Capital Management story as of today. I am very confident that there will be many more chapters in the coming years. I have said little about the role clients have played in our history. Many of you have humbled us with your unfailing trust in the tough times we have faced together. You have sent your friends to talk with us, your children, and your children’s children. You have honored us by asking us to help you work through difficult estate questions. We hold no illusions that we built this company with our own hands. Our clients’ fingerprints are all over everything we do. Even the idea to start a portfolio management company in 1985 came from a client. I also want to recognize the great contributions made by former partners, Tom Lynch and Wayne Ramsey. We rode together for many years, and they added immeasurably to my understanding of both investments, as well as the investment business.