The Quality Doesn't Matter Phenomenon

Standard and Poors recently reported that 2005 was an upside-down year. Their research shows that, in general, the higher the quality of the company the poorer it performed in the year just past. In addition, the smaller the company the better it likely performed. Since when did quality not matter? S&P cited their own research that shows over the long run companies with the highest earnings and dividend quality ratings have outperformed lower quality companies by a wide margin.

But why would “quality” not matter -- especially in a time of increasing globalization, geopolitical risks, rising interest rates, and spiking oil prices? Coincidently, we spent an entire investment policy meeting on this very subject earlier this year. We did not have S&P’s statistics then, but we could see widespread evidence that small stocks were doing better than large stocks. Our conclusion was that the relative out-performance of smaller and less creditworthy companies was a function of the strength of the US economy. The primary reason for that conclusion was that our research showed a similar quality-doesn’t-matter occurrence in bonds; where the yield spread between AAA and junk-rated bonds was also well below normal. We concluded that even though many people (particularly the media) were not buying how strong the US economy was, that US stocks and bonds certainly were.

We started studying this quality-doesn’t-matter phenomenon because we have just been mystified as to why the outstanding business performances of many of the companies we own had largely been ignored. Our world is entirely contained within the so-called investment-grade universe of companies, and those companies were exhibiting three almost universal characteristics: 1. Earning growth that was much higher than the average of the last five years; 2. Dividend growth that was perhaps as good as we have ever seen; 3. Our valuation models were showing most of our companies were 15%-20% undervalued, using statistical relationships between dividend growth and price.

Actually, we were not complaining because these high quality companies were seldom on sale, and we have been nibbling all year, but the strong performance of companies that would never make it through our “quality door” gave us pause. S&P’s recent comments about quality and performance, combined with our own research showing the remarkable narrowing of the yield spread between AAA bonds and junk bonds, produced a kind of “what’s wrong with this picture” among the members of our investment policy committee. This resulted in the following line of thinking: What kind of environment causes riskier companies to perform much better than normal? Answer: when risks are perceived to be low. When are risks to companies low? Answer: when interest rates are low and the economy is strong and expanding. Are interest rates likely to stay low and will the economy continue to grow at near 4%? Answer: no and no.

If our line of thinking is correct, a change in the notion that quality-doesn’t-matter is at hand because we are absolutely convinced that the Federal Reserve’s goal is to slow economic growth to 3% from 4%, and they will drive interest rates wherever they deem necessary to accomplish their goal. A one percent slow down in the economy doesn’t sound like much, but remember it is one percent on 4%, or actually a 25% slowing. That magnitude of slowing will hurt many companies, and it will disproportionately hurt smaller more highly-leveraged companies whose business is mostly in the US; the very companies that the market is currently smitten with.

But doesn’t the slowing economy mean that all companies will suffer? The short and long answers are both “No.” There are three reasons: 1. The typical high quality company that is in our portfolios produces almost 50% of their earnings outside the US. Thus, the slowdown we see coming will be less pronounced among our companies. 2. While the US economy is slowing, economists we follow are forecasting that the rest of the world’s economic growth will be accelerating in 2006. 3. This means that not only will our companies be less affected by the slowing US economy the 50% of their earnings outside the US is likely to be accelerating, which would add to their appeal relative to small domestic companies.

Our research can find few instances where the current quality-does-not matter phenomenon lasted for an extended time. We can find even fewer occasions when quality has actually been a negative, as has been the case in the last 18 months. For these reasons, we believe the current situation cannot last and, indeed, there are signs that the worm is already turning. Since the first of the year, our portfolios have been outperforming the major indexes and, on a total return basis, they have already grown more in the first two and a half months than they did all of 2005. We will keep you informed of their progress in the coming months.

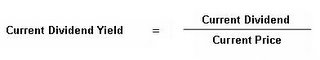

As we said earlier, dividend increases over the past twelve months may have been the best the Rising Income portfolio has ever produced, and we are sure that the portfolio’s dividend growth over the last three years is the best three-year period ever. Currently, there are 27 companies in our model portfolio, which have an average current dividend yield of 3.3%. The big news is that dividend growth over the last twelve months has been 11.6%, with Toyota, Nestle, United Technologies, and Colgate leading the way with dividend increases averaging well over 20%. Dividend increases over the last three years have averaged 10.4%, with Toyota, Cincinnati Financial, Wachovia, Wells Fargo, and United Technologies putting up 20% plus growth.

To compute the total dividend return over the past three years, we add the average dividend yield of 3.3% to the average growth of 10.4% to get 13.7%. During the last three years, the actual total return of the portfolio has been significantly less that this figure, and that is where the valuation gap occurs. Over the last 20 years, on average, the stocks in our portfolio have had a near 90% correlation between dividend growth and price growth. Our models currently indicate that the average stock in our portfolio is 15% undervalued. Our models also indicate that the greatest cause of the valuation gap is the portfolios’ performance over the last year. We believe this is a direct result of the quality-doesn’t-matter phenomenon we discussed earlier, but will change as earnings among smaller companies come up short.

The old saying that goes, “Eventually the cream rises to the top”. Old sayings become old because they are true. We own the cream of the crop. You know the rest.