The Three Buckets of Retirement Income

A wise man once said that people do not choose products and services that they want or need but products that fit the image of who they think they are. That might work when you are trying to keep up with the Joneses, but when it comes to retirement planning, taking the route that Madison Avenue thinks best can be disastrous.

In one ad, the Hartford Insurance Company touts their retirement-planning expertise by having an elk walk past a long trophy case of admiring figurines and out into an empty basketball arena. The voiceover is extolling the underlying theme of trust. Whom are we supposed to trust: a wild animal that has lost its way and wandered into a public building, or an insurance company that believes retirement planning is as easy to produce as the computerized image of an elk? On the other hand, maybe we should trust Merrill Lynch’s bull . . . or maybe not. That bull looks a lot like the same one that we were supposed to follow during the internet stampede. In addition, a website that explains what “Total Merrill” means has the following quote:

“Since there is uncertainty and fear associated with retirement, the Retirement

Visualizer (the Total Merrill ad campaign) will expose users obliquely to the various concepts related to retirement and get at their true feelings and motivations apart from any misconceptions or other ‘baggage’ they may bring with them.”

Okay, that explains everything. It’s one of those “baggage” things. Next thing you know, one of the big financial services companies will bring back the yellow smiley-face and tell us: “Don’t worry. Be happy.”

The Elephant in the Room

Retirement planning for most people is an “elephant in the room” – a question or problem that obviously needs tackling, but is being avoided for the benefit of one or the other party. Because Madison Avenue and Wall Street think people are too afraid and carry too much baggage to tackle it, they want to “obliquely” talk around it and offer up pacifiers and cuteness instead of education and illumination. They say “trust us,” instead of “here are the facts.” They utter benign condescension instead of clarity of thinking.

We have written these quarterly letters for 20 years. We have three filters for what goes in these pages: Is it true? Can we explain it? Is this the one thing that our clients need to hear? To all three of these questions our answer concerning the retirement dilemma is a resounding “Yes.” The time is right, no matter what your age, to look the elephant squarely in the eyes and begin the process of understanding the questions it asks. Because when you do, you will begin to understand what is real and what is an advertising slogan, what you can live with, and what you might be better living without.

We have titled this letter The Three Buckets of Retirement Income. We see those buckets as the answer to the elephant in the room. There is nothing cute or cuddly about a bucket. It is just a container. It has few purposes other than to hold something. As we view the retirement planning strategies offered by Madison Avenue and Wall Street, we see that they are long on “peace of mind” investing but short on how you get there and what you can reasonably expect. The reason is simple – and this is the essence of the “elephant in the room.” Building retirement portfolios that can stand the test of time is very complex, and it cannot be conjured up by some computer-generated model. Things have to work out right for each individual before much peace of mind will bloom, and as we will show, there are no “one decision” investment alternatives at present that offer enough income to allow you to just put the whole matter to bed.

In the following pages, we will lay out the investment alternatives available today, as well as the long-term average returns for each investment class, to give you an order of magnitude for what is probable in the future, as well as possible now.

A One-Bucket Approach: Fixed Income

Let us see what we can expect from the fixed income or bond bucket. In all of our examples, we will assume that you are the proud recipient of a lump sum retirement check of $1 million. That is a lot of money. There ought to be a long list of investment alternatives that can provide a solid living income for a person with that much money. Indeed, there are thousands of investment vehicles, but they each fall into only one of three classes of securities: cash equivalents, fixed income, or equities.

In analyzing the investment options, we will not take into consideration taxes, fees, or the fact that the timing of purchases can change rates of returns dramatically. We are not trying to etch our plan in stone. We are simply trying to provide our educated guess of what the future might look like. In doing so, we are leaning heavily on historical long-term trends.

Short-Term Fixed Income

Let’s look at what a million dollars will generate in cash equivalents. Short-term, no risk alternatives such as Treasury Bills and certificates of deposit have averaged just under 4.0% over the last 80 years. Today they are yielding near 4.5%. By historical standards, short-term interest rates would appear to be a bargain. The only problem is short-term money is short term, and we have little doubt that over the next 20 years or so, T-Bills and CDs will trend toward their long-term average of 3.5% to 4%.

After adjusting for inflation, you would be making little or nothing because inflation has averaged near 3.5% over the last 80 years. In addition, over the last 25 years, short-term rates have been as high as 10% and as low as 1%. If the future is anything like the past, this wide fluctuation in annual interest rates would also mean wide fluctuations in annual income. On an investment of $1 million, that would mean annual income would have been as high as $100,000 and as low as $10,000, with the average being somewhere around $40,000.

In our judgment, this would make income planning impossible and peace of mind in short supply. We believe staying in short-term investments with a large portion of your assets is not a viable option. It places such a high premium on liquidity and preserving capital that it does not allow for a living income, which we believe must be predictable, safe, and if possible, growing.

Long-Term Fixed Income

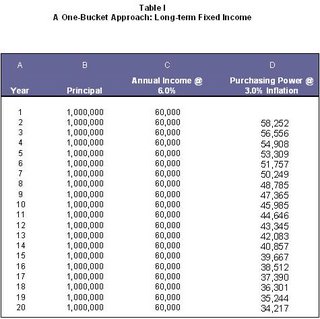

Longer-maturity US Treasury and highly rated corporate bonds have averaged near 6.0% over the last 80 years. While top-quality bonds have recently been yielding 6.0%, longer-term, high-quality bond yields have been moving up in recent months, and we would not be surprised to see them move even higher, unless inflation falls sharply. Since it is possible to obtain 6% yields from lesser quality bonds, and since the long-term average is 6%, we will use that figure for our computations. [double click to increase size]

Table I gives us our first glance at what living out of a fixed income bucket might look like. Because a long-term bond is a form of a contract, we know far into the future how much income our portfolio will produce. If we bought a 20-year non-callable bond with the million dollars, we would know exactly how much we would earn over the next 20 years. We do not recommend that, but history shows us that long-term bonds have provided higher inflation-adjusted returns than short-term investments, and these returns are far more predictable.

From a “living income” perspective, long-term bonds provide predictable income that we believe is safe, but has little chance of keeping pace with inflation. Indeed, a look at column D shows that our purchasing power steadily erodes over time. We think this is a much more troubling situation than you might think. Retirement communities, extended-stay nursing home facilities, and healthcare costs, in general, are rising faster than the average rate of inflation. That means, as you grow older, your health care costs will be rising as your inflation-adjusted income is falling. For this reason, let us move on to another one-bucket approach to see if we can improve our situation.

Before we go there, let us issue a special word of caution regarding annuities. We have seen numerous proposals for annuities that are nothing but a come-on. We are speaking here of annuities that are annuitized (an investor pays a sum of money in return for a lifetime series of monthly payments). We recently spoke with a retiring executive who was offered a 7% return for the rest of his life. That sounds like a good deal until you take into consideration that to get it he has to give up his million dollars. He will receive the $70,000 per year for life, but after he and his wife die, the assets will go to the insurance company. According to government life-expectancy tables, his life expectancy is approximately 20 years. Seventy thousand dollars a year for 20 years has an internal rate of return of 3.4%. This is a terrible deal, but there are a lot of them being offered to people who have difficulty understanding how to evaluate these products.

A One-Bucket Approach: Capital Appreciation from Stocks

Long-term bonds offer better living income than short-term investments, but with bonds, we are always going to be dealing with the loss of purchasing power over a long period. The only way to get around the purchasing power issue is to buy something where the value is going up. Stocks would seem to be a natural here. The total return for Blue Chip common stocks has averaged just over 10% per year for the last 80 years. If we could consistently take a 10% gain each year from stocks, that would obviously generate substantially more income than long-term bonds. We might even get lucky and make more than 10% in some years.

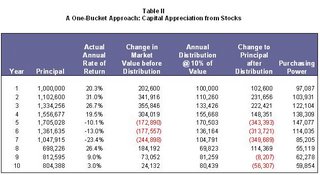

Whoever said you should never mix the words lucky and retirement in the same sentence must have seen our next table. Even though stocks have averaged a 10% rate of return over the long term, the 10% is anything but consistent. [Double click to increase size]

Table II shows a busted retirement program. During the hot years of the late 1990s, the value of the account rose to over $1.7 million, and annual distributions reached $170,000. It has been downhill from there. Indeed, today the value of the account is 20% less than it was 10 years ago, as is the annual distribution. The 10% annual distribution has been greater than the amount earned in five of the ten years.

A lot of money has been pulled out of the portfolio, but it was not earned, and thus was depleting principal. The internal rate of return during this period was more than 9%, but our calculations show that, in order to maintain the integrity of the principal, no more than an annual distribution of approximately 7% could have safely been taken from the account. At first, that may not make sense, but it has to do with the pounding the stock market took in the early 2000s. There are those who say that the three-year bear market may have been like a 100-year flood and is not likely to come again. The problem is, however, there are no guarantees in stocks and trying to live entirely off capital gains, year in and year out, subjects you to the possibility of a busted retirement plan like the one in Table II.

Putting all of your money in stocks, while good in the long run, is almost the antithesis of our concept of living income. The income is not predictable; the principal may be at risk; and it does nothing to deal with the loss of purchasing power. We do not think a stocks-only retirement plan is right for all but the most seasoned of investors. Yet, the startling truth is many of the retirement plans that we see being offered by so-called “retirement planning specialists” have only a token quantity of fixed income securities. Instead, they rely on the illusion that spreading risk among stocks, globally, by capitalization, and by sector can avoid another 100-year wash out.

The Three-Bucket Approach: Fixed Income, Rising Income, and Capital Appreciation

We are convinced that a one-bucket approach of all bonds or stocks subjects a retired person to either a stable stream of income with declining purchasing power or a completely unstable and unpredictable reliance on capital appreciation, both of which will be difficult for most people to stomach.

So, if a one-bucket approach does not work, would a two-bucket approach, relying on some fixed income from bonds and the capital appreciation from stocks, make sense? We believe this two-bucket approach makes more sense than either of the one-bucket approaches but still has some shortcomings. This is because growth stocks produce very little income, which means that almost all of the living income must come from the bonds. Consequently, to achieve an acceptable level of income you are still left with the difficult task of deciding how much capital gains to take (and when) to augment the income from the bonds. In actual practice, our experience tells us that while a two-bucket approach, using bonds and growth stocks, has merit, it subjects people’s “living income” to more risk than they might imagine.

So, if a one-bucket approach has significant problems and a two-bucket approach still has many unknowns, what will work? We call the solution a Three-Bucket Strategy.

At first, the Three-Bucket Strategy may seem a lot like the just-discussed two-bucket strategy because it uses stocks and bonds. The big difference is that instead of using growth stocks and bonds we use rising dividend stocks and bonds, and this makes all the difference. Even though rising dividend stocks are still stocks, they have bond-like qualities. They possess solid financial strength, higher-than-average dividend yield, and a high probability of future dividend growth. All of these characteristics taken together allow us to separate their stock and bond benefits into two buckets – an income bucket and a capital appreciation bucket.

The Three-Bucket Strategy, then, consists of a bucket containing the fixed income from bonds, a bucket containing the rising dividends from stocks, and a bucket holding the capital appreciation created from our rising dividends.

Table III shows, for a 50/50 allocation between bonds and rising dividend stocks, each of the three buckets and how they work together. Bucket # 1 collects a steady and predictable stream of income from bonds or other fixed income securities. Bucket #2 receives a steadily rising stream of income from well established dividend paying stocks. In the table, we are using a dividend yield of 3.2% and dividend growth of 7%, which have been our actual long-term averages. Bucket #3 receives the long-term capital appreciation from the stocks. It certainly will not be as regular as shown, but there is a very high probability, if we do our job right, that capital appreciation will accumulate in Bucket # 3. When appreciation does occur, a part of it is sold and the proceeds put back into Bucket # 1. This keeps the stock-bond ratio in line and increases portfolio income because bonds pay higher income than stocks.

-click on the image to open in a new window, then click "expand to regular size button" at bottom of image for full visibility

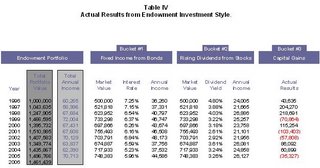

Endowment Investment Strategy – Three Buckets for Real

The last table we want to show you details the actual results of our Endowment style of investment management. Years ago, we coined the name after repeatedly hearing from our not-for-profit clients that they wanted the greatest amount of income they could achieve; they wanted the income to grow at least at the rate of inflation, and they did not want to tap their principal. If you think about it, that is what most of us want in retirement. You will see that the Endowment investment style uses the three-bucket approach. For purposes of illustration, our example is showing a 50/50 split between stocks and bonds. Careful analysis of each person’s situation often pushes the balance toward more stocks or more bonds, but the 50/50 split will give you a good idea of how our three-bucket approach has performed over the last 10 years.

We believe there are three key elements to Table IV that show the how the three-bucket approach answers the living income question.

1. The income is reasonably predictable. In looking at what really happened during an extraordinarily volatile time, not only for stocks but also for interest rates, the Total Income (lighter shaded column) has trended higher, even though the yield on both stocks and bonds has fallen.

2. It is safe. The bond income was produced entirely from investment grade bonds and similar fixed income securities. History shows us that bonds of that quality have an incredibly low default rate. The dividend income was produced by companies that passed stringent tests of financial strength, dividend history, and projected growth.

3. The income and principal are rising. What is remarkable is that during a time when interest rates fell by as much as 30%, the income generated by the portfolio actually rose. How this happened is not entirely explained by Table IV. What you don’t see is that the capital appreciation from the rising dividend stocks was being regularly converted into bonds to maintain the 50/50 stock-bond mix. So, even while interest rates were falling, the transfer of assets from stocks to bonds was enough to allow the Total Portfolio Income to grow. In addition, because this transfer from stocks to bonds happened primarily in up years for the stock market, the effects of the down years were cushioned and allowed the Total Portfolio Value (darker shaded column) to keep growing.

As you can see, tackling the elephant in the room is not about “feel good” and “be happy.” It’s really about math, knowing what is probable and possible, and understanding the investment dynamics of portfolio management.

We have poked fun at the financial services industry and how lightly they are treating what we consider to be a very serious matter – retirement planning and investing. We recognize that you took a lifetime to accumulate your retirement assets. Just as importantly, those assets will have to support you and your family for a long, long time. There is nothing trivial about this. Maybe that’s why we are so committed to getting out the story of the three buckets of retirement income. The story is true. It’s understandable. And, people need to hear it.

Blessings,

Greg Donaldson Mike Hull